October 27th, 2013

With JavaScript approaching near-ubiquity as the scripting language of the web browser, it benefits you to have a basic understanding of its event-driven interaction model and how it differs from the request-response model typically found in languages like Ruby, Python, and Java. In this post, I'll explain some core concepts of the JavaScript concurrency model, including its event loop and message queue in hopes of improving your understanding of a language you're probably already writing but perhaps don't fully understand.

This post is aimed at web developers who are working with (or planning to work with) JavaScript in either the client or the server. If you're already well-versed in event loops then much of this article will be familiar to you. For those of you who aren't, I hope to provide you with a basic understanding such that you can better reason about the code you're reading and writing day-to-day.

In JavaScript, almost all I/O is non-blocking. This includes HTTP requests, database operations and disk reads and writes; the single thread of execution asks the runtime to perform an operation, providing a callback function and then moves on to do something else. When the operation has been completed, a message is enqueued along with the provided callback function. At some point in the future, the message is dequeued and the callback fired.

While this interaction model may be familiar for developers already

accustomed to working with user interfaces - where events like

mousedown, and click could be triggered at any

time - it's dissimilar to the synchronous, request-response model

typically found in server-side applications.

Let's compare two bits of code that make HTTP requests to www.google.com and output the response to console. First, Ruby, with Faraday:

response = Faraday.get 'http://www.google.com'

puts response

puts 'Done!'The execution path is easy to follow:

Let's do the same in JavaScript with Node.js and the Request library:

request('http://www.google.com', function(error, response, body) {

console.log(body);

});

console.log('Done!');A slightly different look, and very different behavior:

The decoupling of the caller from the response allows for the JavaScript runtime to do other things while waiting for your asynchronous operation to complete and their callbacks to fire. But where in memory do these callbacks live - and in what order are they executed? What causes them to be called?

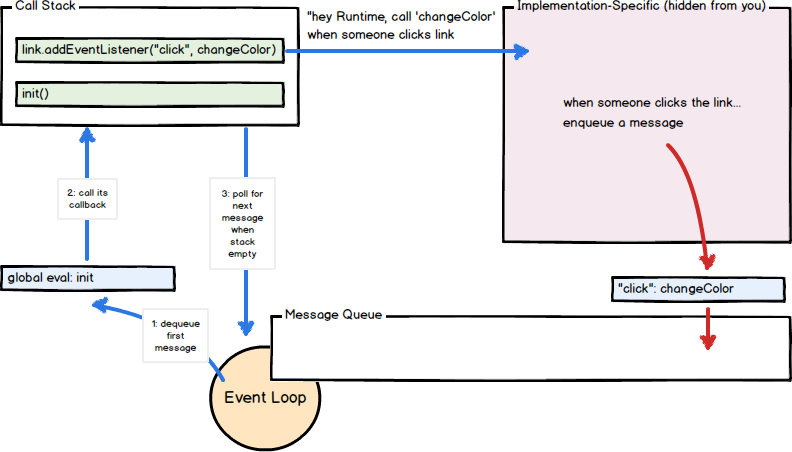

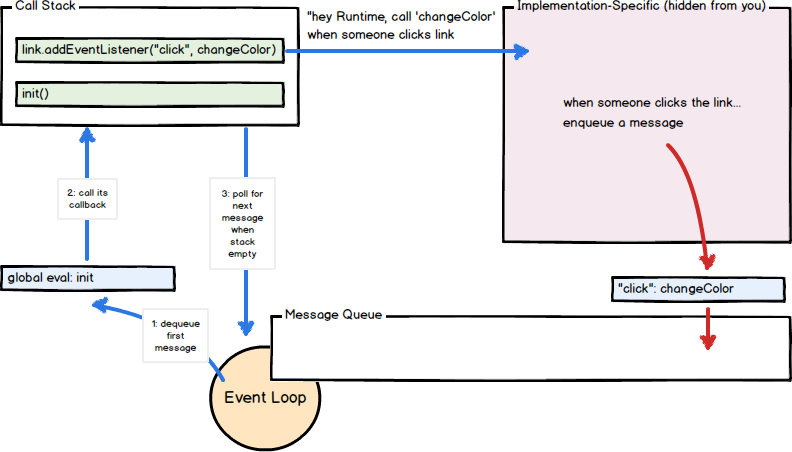

JavaScript runtimes contain a message queue which stores a list of messages to be processed and their associated callback functions. These messages are queued in response to external events (such as a mouse being clicked or receiving the response to an HTTP request) given a callback function has been provided. If, for example a user were to click a button and no callback function was provided - no message would have been enqueued.

In a loop, the queue is polled for the next message (each poll referred to as a "tick") and when a message is encountered, the callback for that message is executed.

The calling of this callback function serves as the initial frame in

the call stack, and due to JavaScript being single-threaded, further

message polling and processing is halted pending the return of all calls

on the stack. Subsequent (synchronous) function calls add new call

frames to the stack (for example, function init calls

function changeColor).

function init() {

var link = document.getElementById("foo");

link.addEventListener("click", function changeColor() {

this.style.color = "burlywood";

});

}

init();In this example, a message (and its callback,

changeColor) is enqueued when the user clicks on the

foo ‘foo' element and an the onclick event

fires. When the message is dequeued, its callback function

changeColor is called. When changeColor

returns (or an error is thrown), the event loop continues. As long as

function changeColor exists, specified as the

onClick callback for the foo element,

subsequent clicks on the element will cause more messages (and

associated callback changeColor) to become enqueued.

If a function called in your code is asynchronous (like

setTimeout), the provided callback will ultimately be

executed as part of a different queued message, on some future tick of

the event loop. For example:

function f() {

console.log("foo");

setTimeout(g, 0);

console.log("baz");

h();

}

function g() {

console.log("bar");

}

function h() {

console.log("blix");

}

f();Due to the non-blocking nature of setTimeout, its callback will fire

at least 0 milliseconds in the future and is not processed as part of

this message. In this example, setTimeout is invoked, passing a callback

function g and a timeout of 0 milliseconds. When the specified time

elapses (in this case, almost instantly) a separate message will be

enqueued containing g as its callback function. The resulting console

activity would look like: foo, baz,

blix and then on the next tick of the event loop:

bar. If in the same call frame two calls are made to

setTimeout - passing the same value for a second argument - their

callbacks will be queued in the order of invocation.

Using Web Workers enables you to offload an expensive operation to a separate thread of execution, freeing up the main thread to do other things. The worker includes a separate message queue, event loop, and memory space independent from the original thread that instantiated it. Communication between the worker and the main thread is done via message passing, which looks very much like the traditional, evented code-examples we've already seen.

First, our worker:

// our worker, which does some CPU-intensive operation

var reportResult = function(e) {

pi = SomeLib.computePiToSpecifiedDecimals(e.data);

postMessage(pi);

};

onmessage = reportResult;Then, the main chunk of code that lives in a script-tag in our HTML:

// our main code, in a <script>-tag in our HTML page

var piWorker = new Worker("pi_calculator.js");

var logResult = function(e) {

console.log("PI: " + e.data);

};

piWorker.addEventListener("message", logResult, false);

piWorker.postMessage(100000);In this example, the main thread spawns a worker and registers the

logResult callback function to the its message

event. In the worker, the reportResult function is

registered to its own message event. When the worker thread

receives the message from the main thread, the worker enqueues a message

and corresponding reportResult callback. When dequeued, a

message is posted back to the main thread where a new message is

enqueued (along with the logResult callback). In this way

the developer can delegate CPU-intensive operations to a separate

thread, freeing the main thread up to continue processing messages and

handling events.

JavaScript's support for closures allow you to register callbacks that, when executed, maintain access to the environment in which they were created even though the execution of the callback creates a new call stack entirely. This is particularly of interest knowing that our callbacks are called as part of a different message than the one in which they were created. Consider the following example:

function changeHeaderDeferred() {

var header = document.getElementById("header");

setTimeout(function changeHeader() {

header.style.color = "red";

return false;

}, 100);

return false;

}

changeHeaderDeferred();In this example, the changeHeaderDeferred function is

executed which includes variable header. The function

setTimeout is invoked, which causes a message (plus the

changeHeader callback) to be added to the message queue approximately

100 milliseconds in the future. The changeHeaderDeferred

function then returns false, ending the processing of the first message

- but the header variable is still referenced via a closure and is not

garbage collected. When the second message is processed (the

changeHeader function) it maintains access to the header

variable declared in the outer function's scope. Once the second message

(the changeHeader function) is processed, the header

variable can be garbage collected.

JavaScript's event-driven interaction model differs from the request-response model many programmers are accustomed to - but as you can see, it's not rocket science. With a simple message queue and event loop, JavaScript enables a developer to build their system around a collection of asynchronously-fired callbacks, freeing the runtime to handle concurrent operations while waiting on external events to happen. However, this is but one approach to concurrency. In the second part of this article I'll compare JavaScript's concurrency model with those found in MRI Ruby (with threads and the GIL), EventMachine (Ruby), and Java (threads).